Readers: How many of you personally know a developer?

Let’s phrase that differently. How many of you personally know someone who has put an addition on their home? Installed a second bathroom? Built a garage or shed, or maybe even added an accessory dwelling unit?

These people are developers, in a sense. Technically, land development has a pretty simple definition: activity that increases the value of a property by building something on it. It doesn’t have to mean starting from a blank slate. And it doesn’t mean you’re the one with all the carpentry, masonry, plumbing, or electrical expertise. The developer is really the project manager, the one who has the vision and then hires all of those people and oversees them.

I’m not being as pedantic as it seems. My point is that there is a whole spectrum of activities involved in the physical development of cities, and at the simplest end of that spectrum is the rehabilitation, modification, and expansion of existing buildings. Historically, in fact, that was a really important way that cities grew. And we’ve kind of gotten away from it to our own detriment.

The vast majority of us today experience the built environment as consumers. The product was made and sold to us by someone else. That would be surprising to people in most of human history, who were also the producers. Barn raisings were big events in farm communities; homeowners put a second story on their own home when they had kids and needed more space; you almost certainly knew the person building on the vacant lot at the corner of your street, because they lived in the neighborhood.

In the modern world, development, like so many other areas of traditional life, has been professionalized and siloed. We’ve made it a very specialized skill set that most of us no longer involve ourselves with. We’ve outsourced the job of creating our cities to Developers with a capital D. And we’re often not happy with the results!

There are good reasons to have a class of professionals who really know the ins and outs of building, of course. Just as most of us find it good that we don’t all have to be expert car mechanics, but can simply take our car to one for repairs as needed. Buildings have higher safety and quality standards than used to exist, and freeing up what wasn’t necessarily time people of the past chose to spend. (While a lot of very old buildings are extremely robust, the ones you see standing today are a skewed sample that excludes all the ones that have already fallen apart or been demolished for good reason!)

But what if we had a class of semi-amateur developers 10 or 100 times larger than it is today? That would still mean that the vast majority of people aren’t doing development themselves. But it would mean the potential for 10 to 100 times more small projects that are neighborhood-enriching and fill gaps: the vacant lot infill project, the historic building renovation, the duplex or fourplex conversion, the corner store or ACU, and so on.

How many people do you know who have considered doing a neighborhood development project. “What if I were the one who bought that vacant lot? What if…?” I guarantee it’s a lot more people than will go through with it, because the prospect is daunting. What would it mean for our neighborhoods if more of them felt equipped and empowered to pursue those dreams?

It can be done. And it can scale.

Triple-deckers in Boston.

Chicago added a million people between 1850 and 1890, and another two million by 1930. How did 19th century cities grow in the staggeringly fast way they did without a huge class of professional developers, architects, planners, etc? The answer is amateur developers.

Read: Incremental doesn’t mean slow.

The Boston triple-decker is a beloved housing type in New England because of its early (small-d) democratic appeal. For its owners, many of them working-class immigrants, it was a path into the middle class: you could own the building, live in one unit, and rent out the other two. The many thousands of these built in the late 19th and early 20th century were largely not built by professional developers, but by casual investors, factory and mill owners, and small-time carpenters.

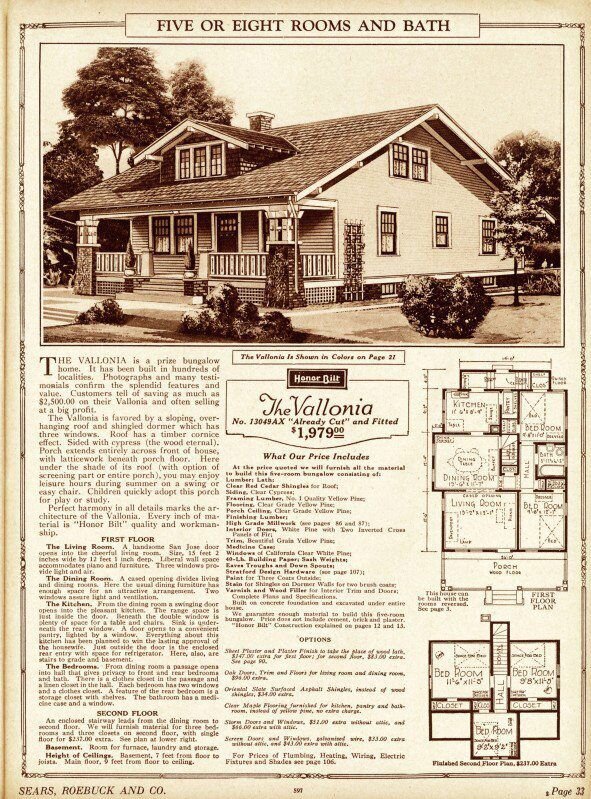

Sears / Roebuck bungalow catalog page from the 1920s.

In the early 20th century, this “swarm” of amateur developers met modern technology in the form of the Craftsman catalog phenomenon. You could mail-order an entire house, and all of the building materials and instructions would be shipped to you. The labor was on you, and probably meant your cousins and neighbors. Craftsman bungalows became the essential building block of the streetcar suburbs, and they still dominate some tremendously beloved neighborhoods today. (Though our historical memory of how those places were seen at the time is highly selective.)

What might the modern version of the Craftsman phenomenon look like? I’m not the best one to speculate, but we have more modular and pre-fab construction techniques available to us today than a century ago. We have companies like Dweller or Maxable that help homeowners develop accessory dwelling units by taking over the parts of the job they don’t feel equipped to do. These are models that could expand and evolve, if there were a bigger market for them.

Even as late as the 1960s, incremental development was still thickening up the urban fabric in places that weren’t in outright decline by then. A 1964 book called The Low-Rise Speculative Apartment by Wallace Smith describes this phenomenon as it appeared in Oakland, California (I learned of it from this excellent thread by Twitter user TribTowerViews). Small-time developers in the 1960s built hundreds of small apartment buildings on scattered lots around Oakland, many of them replacing older single-family homes. At least 1/3 of these developers appeared to have no real-estate industry ties, and by and large these projects did not involve the practices—such as land assembly—typical of corporate developers who build at larger scales.

What killed the swarm?

A wave of downzonings in the 1960s and 1970s banned this practice in many American cities—a regulatory trend only now beginning to be reversed in places such as Minneapolis, Portland, and Sacramento.

But zoning aside, the general decline of cities in the postwar era no doubt had the biggest role in killing amateur incremental development. With virtually no market in the shrinking cities of the East and Midwest in the 1950s through 1970s, a generation’s worth of experience and institutional knowledge of how to do urban infill development was lost. At the same time, you could argue there’s some causality in the other direction too: we subsidized industrial-scale, hyper-efficient suburban development to a degree that it sucked up all the market demand and crowded out the inefficient (from a narrow, profit maximizing standpoint) work that small operators might be doing.

A little inefficiency is our best friend here: we’d have more resilient cities if our cities had more developers. Not a little more but 100 times more.

Bring back the swarm.

Unleashing the swarm is key to a more resilient urban future in a number of aspects:

Unleash the swarm to alleviate housing shortages.

A major cause of housing problems in high-cost cities is the reliance on a small number of huge development projects to meet demand. This has bred a culture in which individual projects become lengthy, high-stakes negotiations with the local government. This dynamic turbocharges Not in My Backyard sentiment and other sources of local opposition, and the resulting delay imposes real costs that raise the price of housing.

If we get a “swarm” of incremental development projects of the type envisioned by initiatives like Portland’s Residential Infill Project, it will be in large part because such development is occurring as of right—no public hearing, no byzantine permitting process.

Read: Nolan Gray on as-of-right development.

Read: Daniel Herriges on what happens when a few companies dominate the housing market.

Unleash the swarm to spread investment to less-hot markets.

Big developers go where the biggest money is. The result is a Trickle vs. Fire Hose effect: a handful of hot neighborhoods are flooded with investment, while many more languish. The incremental developer’s calculus is different. In a somewhat cooler market, you might have a neighborhood people love and care about and want to see advance to the next level, where there simply aren’t any $20 million development opportunities—but there are a ton of $500,000 development opportunities. Or $100,000 opportunities, like the renovation of an old house.

Read: ”The Trickle or the Fire Hose.”

Read: ”Gentrification and Cataclysmic Money.”

Unleash the swarm to revitalize neighborhoods without gentrifying them.

Incremental development is a crucial way to align a neighborhood’s growth with the interests of the people who actually live there, because incremental developers operate close to the ground. They know the people around, they know highly-specific local needs, and in many cases they live in the neighborhood themselves.

Watch or listen: Derek Avery interview on revitalization without gentrification.

Read: Joel Dixon on using development to rebuild wealth for the people who live in a neighborhood.

Unleash the swarm to achieve a fine grain and a human scale.

Increasing the number of decision-makers in our cities and neighborhoods has a myriad of benefits. With large-scale development, the decisions that shape our places are in very few hands, and any mistakes those developers make are magnified.

Read: Daniel Herriges on cities shaped by many hands.

Read: Kevin Klinkenberg on the value and importance of small urban lots.

Become part of the swarm.

For more Strong Towns resources on incremental development, check out our new Action Lab. There you’ll find our cornerstone articles on incremental development, case studies and examples, and practical information on how to become an incremental developer yourself.